The VC space tends to be quite opaque. A conversation with a friend looking to get into VC made me realise how much I’ve learned in my short 1.5-year journey. So I got inspired to write this!

Note: If you’re in VC, these are going to be blindingly obvious

Fund size matters. Larger fund =/= better fund

Before VC, I thought the best VCs are the ones raising multi-billion dollar funds. But in reality, there is a “sweet spot” for funds depending on the stage they invest in — early stage lead VCs (pre-seed - Series A) tend keep their fund size small ($25-125M) so it’s more feasible to return the fund (25-30 $1-4M cheques in 3-5 years). This means there’s no point raising a $1B fund if you’re doing pre-seed and seed.

One of the best funds of all time, Hummingbird Ventures only raised €20-40M for their first three funds, even though they had already returned 7-10X DPI. It takes discipline to maintain a small fund size, especially because it’s enticing to raise a big fund, get paid the 2% management fees and sit back & relax.

It’s usually not the best for startups to raise at the highest possible valuation

Let’s say a founder needs $3M and goes to market to raise a $3M Seed at $15M. While fundraising, the bull market hits and investors start offering them $5M at $30M. While this looks good on paper (less dilution, more money, higher valuation), the founder is now forced to grow even more quickly, otherwise he/she will struggle to raise the following round at a valuation higher than $30M.

Furthermore, when a bear market hits, the founder might be forced to raise a flat or down-round. This is usually a death spell to startups as it kills the team’s confidence and sends a negative signal to the market. Typically, startups should only raise the min amount needed + some buffer.

Many cap tables are dead on arrival

If you sold 50% of your startup at pre-seed because “at that point it was just an idea”, you’re going to find it very very difficult to raise the next funding round, even if you’re a great founder with an amazing product.

VCs typically want (co-)founders to still own >50% while raising a Series A — back-solving this means Founders should sell only 10-15% at Pre-seed and 20-25% at Seed. The size of rounds also depends on how capital-intensive your startup is — for example, if you’re launching an Exchange, you’d probably need to frontload quite a bit of cost to build it out. Note I use “typically” as you would find anomalies everywhere — Mistral AI recently raised a $113M seed round at $260M valuation.

VCs typically have to fight for stellar founders to take their money

Before VC, I’d think that VCs are the boss since they have the money. Startups are the ones who should be begging VCs to fund them. What actually happens a lot of the time is that too many VCs want to invest in a stellar founder. Money is a commodity. So here the tables turn and the VCs end up pitching their value add to the founder. Having a good brand and strong track record as a VC here is crucial.

Early stage valuations are just “finger-in-the-air” estimates

People always ask how you value startups with zero revenue. You simply start at a benchmark, i.e. Pre-seed rounds at $5-15M, Seed at $10-25M, Series A at $50-100M. From there, you increase or decrease it based on the founder, traction, PMF, etc.

Valuations are just a supply (startups) & demand (VCs) game. US deals tend to be much more expensive than European ones as there is just much more demand (VC capital) than supply (good startups). Even with these handwavy metrics, most VCs end up valuing start-ups in a similar range.

A VC’s DPI is the only metric that matters to their investors

The best metric to measure VCs is DPI, or “Distributed-to-paid-in”. This is how much cold hard cash a VC returns to their investors. VCs typically target >3x DPI, which means if you invest $5M in my VC fund, I’ll return you at least $15M in 7-10 years. There is a great analysis by Altimeter which shows that the top quartile of fund’s average DPI is only 1.7x. Only the top 10% of VCs return >3x DPI as a VC’s performance also follows the power law where the top 0.1% like Hummingbird return 7.5-10x.

TVPI and DPI of top quartile VC funds (Chamath’s Substack) You need to be Contrarian and Right. And that’s difficult.

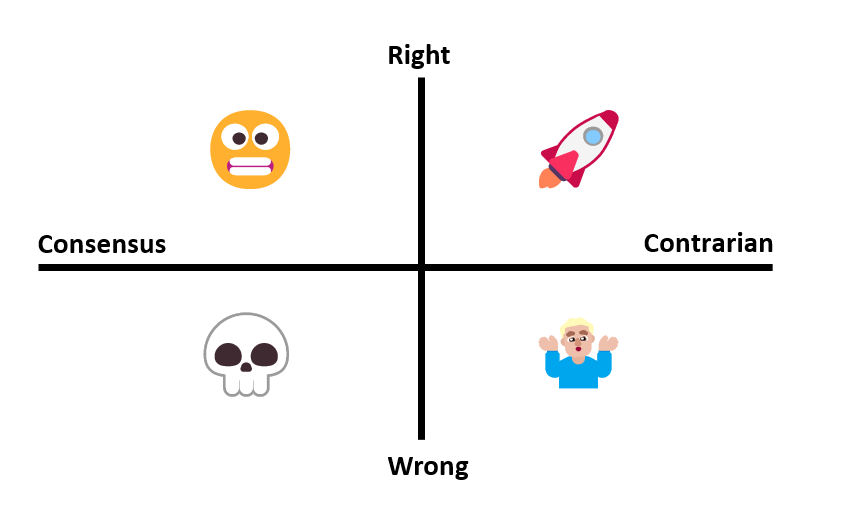

Legendary investor Bill Gurley once said, “What most people don’t realise is if you’re right and consensus you don’t make money”. You can’t be part of the crowd and still beat the crowd. Within crypto, being non-consensus is investing in Coinbase in 2012/13 (USV, Ribbit, Garry Tan) when Bitcoin was $100 or investing in OpenSea in 2018 (1confirmation) when “NFTs” weren’t even a thing.

Being contrarian is difficult because you’ll feel dumb for a long time, as it takes time for contrarian theses to play out. It’s much more comfortable to invest in consensus themes because you will feel smart in the meantime, although it is difficult to make outsized returns(😬). On contrarian bets, you’ll feel dumb and be wrong 9 out of 10 times, which is totally expected (🤷🏼♂️), but it’s the 1 successful contrarian bet that will return your fund (🚀). If you’re in a consensus vertical and still invest in the wrong companies, then… 💀

You need to be super optimistic and open-minded to be a VC

Given the need to be non-consensus, startups that VCs look at are going to be incredibly early and niche where there are 101 ways things could go wrong. VCs will need to really squint to see how this fresh new idea could work, and how everything could go very right instead.

A pessimist would tell you there are 101 reasons why Airbnb wouldn’t work. Renting a room in your house is so unsafe and how would regulations react to it? If that were you, congratulations, you have passed on the opportunity to turn $150K into $11.5B. In any case, don’t worry as you are not alone.

Crypto itself would be considered contrarian to many generalist VCs, but to be contrarian among crypto VCs is even more difficult. Here, I’m actively exploring sectors such as Decentralised Science, Urbit, and Network States.

And that’s all for now. Happy new year!